Saint Dominic: An Evangelical Man

SAINT DOMINIC: AN EVANGELICAL MAN

St. Dominic is a man of yesterday and today. After 800 years of evangelical mission, his presence is still alive among us, his sons and daughters; his memory is constant and his teachings vital. We find in him a Master of spiritual life, a Father who exhorts us to follow in his footsteps.

The more we know him, the more we love him.

In the twenty-first century, we continue to be moved by his humanity, his sensitivity and his dynamism.

Before birth, he was already destined to be an inflamed torch that burns the world. His life was a continuous ascension bathed in the clarity of God. Around Dominic, a zone of light was woven, that source of spiritual rays that generates radiances of faith, of the reflection of the “light” of Christ. Dominic is above all light, and this light is reality and symbol generating wonders; the light is innovative, reforming, and revolutionary, which through the ages has projected a clarity such that many have devoted themselves to following in his footsteps.

Jordan of Saxony tells us that Dominic illumined “those who sit in darkness and in the shadow of death” (Libellus 9).

His whole life is a sign, a manifestation of the Spirit. Revelation gives us the key: “The Spirit and the bride say, Come Lord Jesus. Whoever hears say come, whoever is thirsty should come and receive the water of life for free.” Thanks to His Spirit, we can drink the water of life for free, as we so often repeat, “Give us ‘the water of Wisdom.'” Those of us who find in him a model of Christian life feel called to live as he lived; he has left us a great example to follow and imitate.

He was an evangelical man. He lived the Gospel.

Three Axes of Dominic’s Life

His whole life revolves around three axes: apostolic zeal, common life, and incessant prayer.

1. His great apostolic zeal: It led him not to miss the opportunity to proclaim the Gospel, as his witnesses attest. Among many of them, we highlight this testimony of Fray Juan de Navarra. “Dominic took pity on his neighbors and ardently desired their salvation. Many times he preached the same, induced and sent the friars to preach, begging and admonishing them to be diligent in the salvation of souls.”

His whole being and living was moved by the light and fire of the Holy Spirit, attentive to the Word of the Lord he heard in his heart, “Go and tell them what I command you. Do not be afraid of them, I will be with you” (Jer. 1:4). He was like St. Paul who felt in his heart the experience of the Spirit, saying, “Woe to me if I do not evangelize!” Guided by the Spirit and open to God, he gave himself to free and to gather the scattered children of God. For Dominic, eternal salvation is not a hollow word; he cannot resign himself, but he mobilizes himself to save them: it is his main concern. He is a passionate man; he loves Christ and all men. St. Dominic was a man of flesh heart and was sensitive to the material and spiritual needs of men.

Brother Stephen, one of the first witnesses who lived with him, tells us, “At that time a terrible famine began to waste the region so that many of the poor were dying of hunger. Moved by compassion and mercy, Brother Dominic sold his books (which he himself had annotated) and other possessions, gave the money to the poor and said, ‘I will not study on dead skins when men are dying of hunger.'” (THE PROCESS OF CANONIZATION AT BOLOGNA, 35). His first trait is mercy; his great personality is compassion; he lived constantly in that inner attitude that put him in communion with the misery of others.

Jesus was full of compassion, suffered with those who suffered, shared their sorrow, and transmitted that sensitivity to his disciples. Jesus, sensitive to the hunger of the crowd, multiplied the loaves and fish. Dominic gives what he has. He goes to the most needy; he does it from the heart; he fights the misery of others, both material and moral. Dominic has received from the Holy Spirit the gift of participating in the suffering of others. He is a man of extreme sensitivity, making “the passion of Christ his own.” He suffers because God is not loved by all men. Compassion changes his life. He couldn’t go far before the misery of others without feeling moved. Dominic establishes the apostolic life according to the example of the apostles. He wants his vocation not to be for himself, but all his desire is to be LIFE FOR OTHERS. His vocation is to imitate Christ as preacher of the Gospel. Our Father wants his sons and daughters to participate in this compassion, to make it our own, and to give men in the face of their material or spiritual misery the response that springs from the heart of God.

He tells us that in order not to lose this sensitivity and our true reason for being, we ought to love poverty, which leads us to seek God and to be in need of Him, to put everything in His hands, and to labor for Him and fill our hearts with His love. He opts for the life of poverty for various reasons. Poverty leads us to the freedom of preaching, to the availability of apostolate, and to the imitation of Jesus. The vitality of apostolic life depends on poverty. To be an Evangelical man, you have to be poor.

Furthermore, the word filled his whole life. Dominic was the ultimate guardian of souls; he recognized that only the authentic word can save, and that, thus, it was necessary to announce it. His word was convincing because there was consistency between his words and his deeds. Truth is the axis of his life: he spoke out of the abundance of his heart. Dominic immediately realized that the conversion of heretics was not an intellectual problem, but a problem of inner brokenness. His preaching was like a double-edged sword. It was the Spirit who spoke through his mouth. His principal aim was not so much in convincing but in breaking the heart of stone. He acted out of compassion.

In his preaching, there are not only fruits and miracles, but also misunderstandings, rejections, and even persecutions abounded. St. Dominic, like St. Paul, bore witness to Jesus Christ through sufferings. His great apostolic zeal led him to preach from the Spirit, that is, spontaneously, in pure faith, entrusting the word to the action of grace; he preached from prayer, faith and trust. He knew the gratuitousness that had been given to him: the word was continually given to him, it was the action of God in him.

In the today of history, we have to preach Jesus Christ, we have to be light and leaven for all men living–these two identities correspond to the double contemplative–apostolic foundation of our life. From our daily life, with its difficulties, we live everything FROM LOVE AND WITH LOVE. It is the Spirit who carries it out. We must be like a feather carried by a powerful breeze, a channel through which the Lord can freely let a current of grace flow that will transform others. It is to rest in the Lord by accepting his initiative. Dominic surrendered as Mary did, saying, “Lord, let it be done to me, according to your will.”

2. The common life: It is the characteristic of the foundation of the Order. He saw, in founding his Order, that it was a manifestation of the Spirit for the good of the Church and of men. As a work of God’s grace, everything came from Him. The experience of grace, in which everything is received, produces humility.

Our constitutions, the laws of the Order, do not oblige under sin: their fulfillment must be anointed only by the inner grace and responsibility of the individual. The law is not despised but is a channel of spiritual and human coexistence. Salvation does not come from the fulfillment of a law but from the gratuitousness of Jesus Christ.

The community of friars and sisters live in dialogue, fraternity, the sharing of goods, in chapters, and in the common celebration of the liturgy. Dominic wants an organization based on the free expression of the personality of each one. Dominic imprinted on his Order a novel and original style. It focused on the fundamental values of respect for a person’s dignity, of representativeness, and of co-responsibility–all based on faith. Our Father founds the Order around community life and, from here, everything revolves. He chooses the Rule of St. Augustine, which is founded on the model of the Church of the first Christians in Jerusalem and of the need for unanimity in common life. “The first goal for which you have gathered in community is that you may dwell in the house unanimously and have a single soul and a heart toward God. And do not have anything as your own but let everything belongs to everyone” (Rule of St. Augustine). St. Dominic insists: the life of the apostles is essential. He wants his friars to live together, to pray together, and to go preach together. We have several very precious testimonies of the qualities of Our Father for common life.

In the Bologna Canonization Process (#17), it is recorded: “On August the eighth, Brother Amizio of Milan, priest, prior at Padua, stated under oath that Master Dominic was a humble and meek man, patient and kind, quiet, peaceful and modest. There was a solid maturity in all his actions and words; he was a sympathetic consoler of others, but especially of his own brethren. He had an ardent zeal for regular observance…[and] great love for poverty…” (Bologna Canonization Process). Also, Brother Paul of Venice deposed: “[Dominic] was the best possible comforter of the brethren and others in trouble or temptation. He [Brother Paul] knew this both because he experienced it himself and also heard the same thing from others.” (Bologna Canonization Process #43).

He had the charism of the spiritual companion. He was not content to attract friars to his Order, but was committed in them to help them at the time of trials. For St. Dominic, common life is not limited to living together. To live it well, unanimity is necessary, in the collective commitment of common life. “What has to be lived by everyone, has to be decided by everyone.” Common life can only function well if there is a total surrender, a giving of oneself totally to others, without a spirit of the reward-seeking. It is to give everything that I have received, to live the evangelical confidence of losing everything to gain everything. As he tells us, there is more joy in giving than in receiving. To live this requires a great strength of soul, as Our Father Dominic had. “All men were swept into the embrace of his charity, and, in loving all, he was beloved by all.” (Libellus #107) He considered it his duty to rejoice with those who rejoice and to weep with those who mourn. He carried this out from his piety, devoting himself to the care of the poor and wretched. Community life is a source of joy, the joy promised by the Lord, which the world cannot comprehend.

St. Dominic knows how to command because he has known how to obey. He knows how to decide because he has been able to mature. He doesn’t think about his personal success; he has forged himself in the inner life. He did not live according to logical reasons; he acts guided by the Holy Spirit. St. Thomas tells us, “Those who are moved by divine instinct should not be advised by human reason, but should follow the inner inspiration that comes from a higher principle.” St. Dominic transmitted to his children the greatness of mind, and to us he continues to transmit it, trusting in the grace of God that guides us. “Fully trusting in God,” says John of Navarre, “He sent to preach even the less skilled, telling them, Go confidently, for the Lord will give you the gift of the divine word, he will be with you and you will lack nothing. They would go out to preach, and everything happened as he had said.” Jordan of Saxony, who lived with St. Dominic closely, portrays Dominic as a man, a brother, and a Father; Jordan praises that Dominic’s presence impressed, touched the hearts of those to whom he addressed. He listened because he loved. He knew how to be brothers of all. He was first and foremost a Father. He has begotten many sons and daughters. He loved as a father, and he was loved as a father.

Our constitutions tell us that we are summoned into the community “to have one soul in God.” We form a community, each one summoned by Jesus Christ to make our own the cause of the Kingdom of God: “I have heard the cries of my people and I have not been able to bear them, so go and tell them”. We live in community by listening to the voice of God who summons us from the burning bush of his Word and from the groans of his people. A Monastery in the middle of the village makes present now and here the Kingdom of Heaven. Similarly, a Community is the Temple of the Holy Spirit; it is a Mystery that must lead each to see the Mystery of God. Our relationships have to be spiritual; we are inhabited by the Trinity. Community life is a work of God. When we build communion, welcome, generosity, listening–where we make the feeling of others our own–when we offer a witness of faith, of trust, in the hope that comes to us from Him and gives light to us, we become LIFE FOR OTHERS.

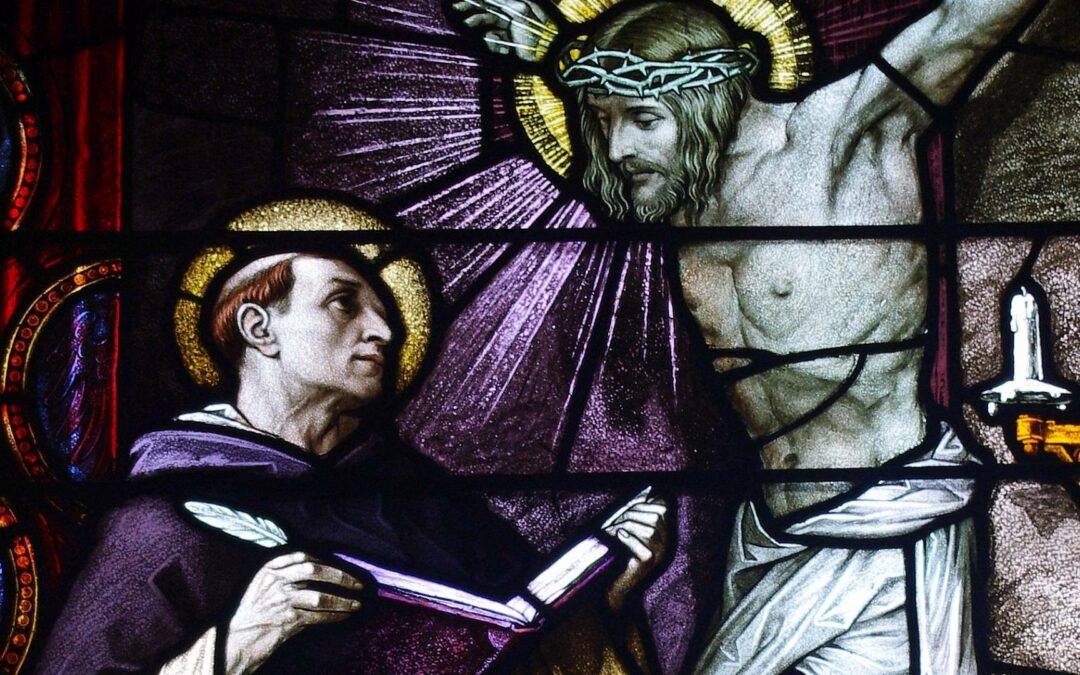

3. Prayer: It is that element that gives life to apostolic zeal and common life. All those who lived with St. Dominic insisted on the intensity of his prayer. He prayed as he breathed; he was invaded by prayer; he prayed incessantly, so much so that when he went on his way, he did not stop praying so as not to lose contact with the Lord. In an almost uninterrupted conversing with Christ Crucified, he always carried with him the Gospel of St. Matthew and the letters of St. Paul.

His dialogue with Christ always has, as its horizon, the souls for whom Christ has given his life. Brother William of Montferrat deposed that “whenever it was time for [Dominic] to go to bed, he first applied himself energetically to prayer, sometimes with groans and tears, so that often he woke the witness and the others from sleep with his groaning and weeping. And he firmly believes that he spent more time in prayer than in sleeping…He refrained from idle words and spoke always about God or with God.” (Bologna Canonization Process #13, translated in Dominic authored by Koudelka OP, Tugwell OP, and Fissler OP). He immersed himself in prayer like a child according to the Gospel. As a lamp that shines in the night, he practiced the spirit of what the Lord says in Luke 21:36: Be vigilant and keep praying.

St. Dominic prayed with body and soul, with all his being. He lived a deep communion with those who suffered. His prayer is first and foremost imitation of the praying Christ, and the prayer of Christ reaches its perfection on the Cross, because, for prayer to be life, it is necessary to pass through the cross, embrace it, and stick to it. He liked to pray standing, with the hands open, as a sign of oblation, as one who receives everything, as one who draws from the open heart of Jesus the water he needs to live. He loved the Lord, being in a deep union with Him. He was a man of deep faith; he had a great love for God and neighbor; he was dominated by an impetus of divine fervor; he lived out of his intense interior life. The theological life that he lived in depth expressed itself in joy, the true fruit of charity. This gift of joy that comes from God manifests itself even after his death: in that aroma spreading from his body during its translation to a new sepulchre. The joy he lived on earth is now spread by that good smell. That perfume spreading from his remains is presented to us as a confirmation of his theological life.

St. Dominic was a man of prayer and word. The Word has forged in him the inner man; he has been able to mature so as to act not in function of himself but in favor of others. When he read Sacred Scripture, he gave himself entirely to meditative reading; he gave himself to it as if he gave himself to people. The Gospel to him was a person. His mind lit up sweetly as if he heard the Lord speaking to him. And as he met people, he perceived it to be meeting Christ, and his heart burned in fire to preach to others. His spiritual life was centered on the celebration of the liturgy. The liturgy was lived as the public expression of the intimate divine life of the Church. God chose the Incarnation to communicate with man, using human language that is based on words and signs. God is in permanent and sensitive contact with men. He entrusts to us the Liturgy, this permanence of praise and intercession. Living the whole divine office, we actively participate in the end of our Order which is the salvation of souls.

Dominic’s great experience of knowing himself loved and saved led him to passionately proclaim Jesus Christ, not as an object of devotion but as the one who appears and changes your life. Our contemplation has to lead us to the line of truth, which is our motto VERITAS. It is the Spirit-infused knowledge of the mysteries of our salvation. St. Dominic teaches us that truth is as important as love to penetrate the soul. The whole meaning of our life is in the truth in the line of the good and love.

Before leaving this world, Our Father left us a message of truth and love. It is a magnificent testament of hope, and the commitment to live this inheritance, we his sons and daughters must never forget. He is always among us; he promised us at the hour of his death, “I will be more useful and profitable after death than I have been in life.” And he wants us to think about what it is to be poor, humble and charitable: to be witnesses for others of the LOVE OF JESUS CHRIST.

The boundary between humans and non-human animals has been an integral part of philosophical discourse since antiquity. Attempts to draw a boundary between human and nonhuman life has involved the literary imagination as well as philosophical reflection. Throughout the centuries philosophers and poets alike have defended an essential difference – rather than a porous transition – between what counts as human and what as animal. The attempts to assign essential properties to humans (e.g. a capacity for language use, reason and morality) often reflected ulterior aims to defend a privileged position for humans with regard to animals (which were, in turn, interpreted as speechless, irrational and amoral). While this form of humanism has come under attack through animal rights initiatives in recent decades, alternative ways of engaging the human-animal relationship from a philosophical and poetic perspective are rare. The conference thus aims to shift the traditional anthropocentric focus of philosophy and literature by combining the question “what is human?” with the question “what is animal?” to explore productive ways of thinking with and beyond the human-animal boundary.

The boundary between humans and non-human animals has been an integral part of philosophical discourse since antiquity. Attempts to draw a boundary between human and nonhuman life has involved the literary imagination as well as philosophical reflection. Throughout the centuries philosophers and poets alike have defended an essential difference – rather than a porous transition – between what counts as human and what as animal. The attempts to assign essential properties to humans (e.g. a capacity for language use, reason and morality) often reflected ulterior aims to defend a privileged position for humans with regard to animals (which were, in turn, interpreted as speechless, irrational and amoral). While this form of humanism has come under attack through animal rights initiatives in recent decades, alternative ways of engaging the human-animal relationship from a philosophical and poetic perspective are rare. The conference thus aims to shift the traditional anthropocentric focus of philosophy and literature by combining the question “what is human?” with the question “what is animal?” to explore productive ways of thinking with and beyond the human-animal boundary. The Singapore-Hong Kong-Macau Symposium on Chinese Philosophy took place on 29-30 April 2016. It aims to foster dialogue and interaction among scholars and advanced graduate students primarily based in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Macau. Topics include any aspect of Chinese Philosophy, as well as papers dealing with comparative issues that engage Chinese perspectives. While preference is given to those from the region, participants from any geographic areas are welcome. Organised and sponsored by the Department of Philosophy, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The Singapore-Hong Kong-Macau Symposium on Chinese Philosophy took place on 29-30 April 2016. It aims to foster dialogue and interaction among scholars and advanced graduate students primarily based in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Macau. Topics include any aspect of Chinese Philosophy, as well as papers dealing with comparative issues that engage Chinese perspectives. While preference is given to those from the region, participants from any geographic areas are welcome. Organised and sponsored by the Department of Philosophy, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.